Creating a Serious Game to Support Discussions about Cognitively Supportive Home Design

(led by Professors Vikki McCall and Alasdair Rutherford).

How would you convince people with very different perspectives to see each other’s side of an argument?

How you answer that question will vary quite a bit depending on your experience. A teacher working with young students will use very different tactics to a UN representative trying to convince different countries to come together to respond to a particular problem, for example.

Work Package 4 focused on designing a tool that could help people from different backgrounds with different needs and priorities come together and explore the challenges associated with designing homes from healthy cognitive ageing from different perspectives.

The result was Our House- a Serious game based in empirical evidence, co-designed with older people, that has been designed to help players not only listen to different views, but put themselves in the shoes of different others to get a better understanding of how these different perspectives can shape every aspect of creating an age-inclusive home.

What is a serious game?

A serious game is simply a game that is designed to be used as a tool help the players achieve a particular outcome. Serious games focus on achieving a particular goal, rather than entertaining the players. As a result, many serious games are designed to be educational, or to help players learn or improve a particular skill, or to help them develop a new habit.

If you’ve played a realistic flight or train simulator or used an app to make a game out of starting to run regularly, you’ve probably played a serious game.

What did DesHCA do?

The serious game was designed and refined throughout the DesHCA project, drawing on insights from each of the other work packages as they became avaliable. DesHCA’s Community Researchers played a key role in developing the game, working closely with Professors Vikki McCall and Alasdair Rutherford to ensure the concerns and perspectives of older people were kept at the very heart of Our House, DesHCA’s evidence based serious game.

Since development, Our House has been played with over 120 participants from a range of backgrounds, including those working in housing associations, local government, architecture, health and social care, and the third sector.

How does "Our House" work?

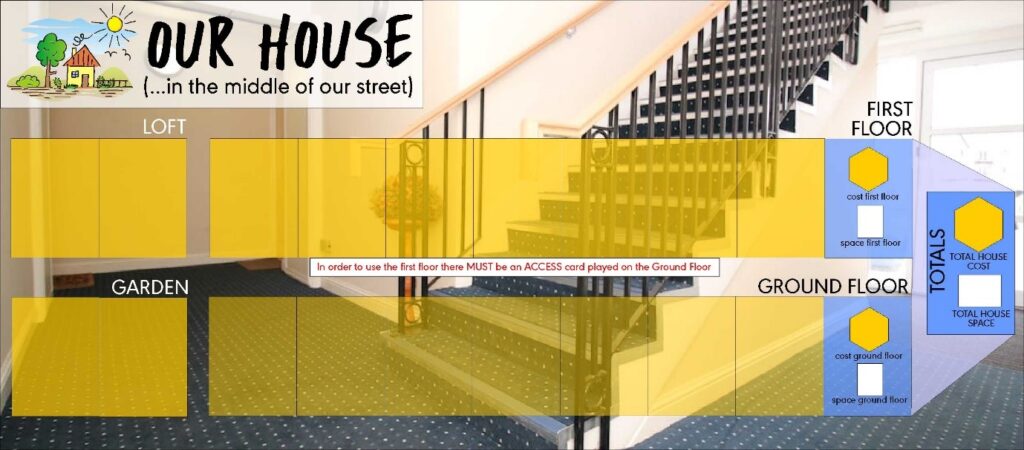

The main version of the game is played in person, with anywhere between 6 and 40 players at a time. Players are split into teams of two and given a short ‘practice round’ where they use the cards to build their own house- allowing them to get a handle on the basic mechanics of the game before play really begins.

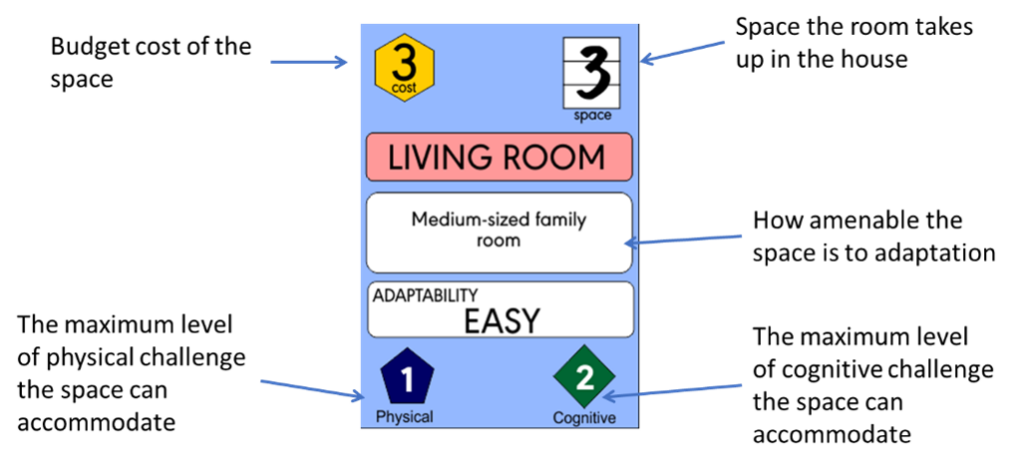

The Our House cards have several key features including a cost and a physical and cognitive score.  Players ‘build’ homes by placing these cards on the Our House board, keeping track of cost as they go.

Players ‘build’ homes by placing these cards on the Our House board, keeping track of cost as they go.

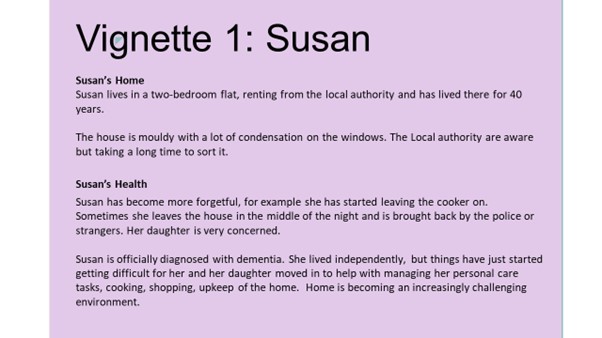

The game begins properly when players recieve their vignette- a short story that describes a fictional household, based on the data and stories collected by the DesHCA project. The vignette they recieve shapes the rest of their game as it outlines their budget, the house they start in, and the needs of the person they’re playing ‘for’, like Susan in the example below:

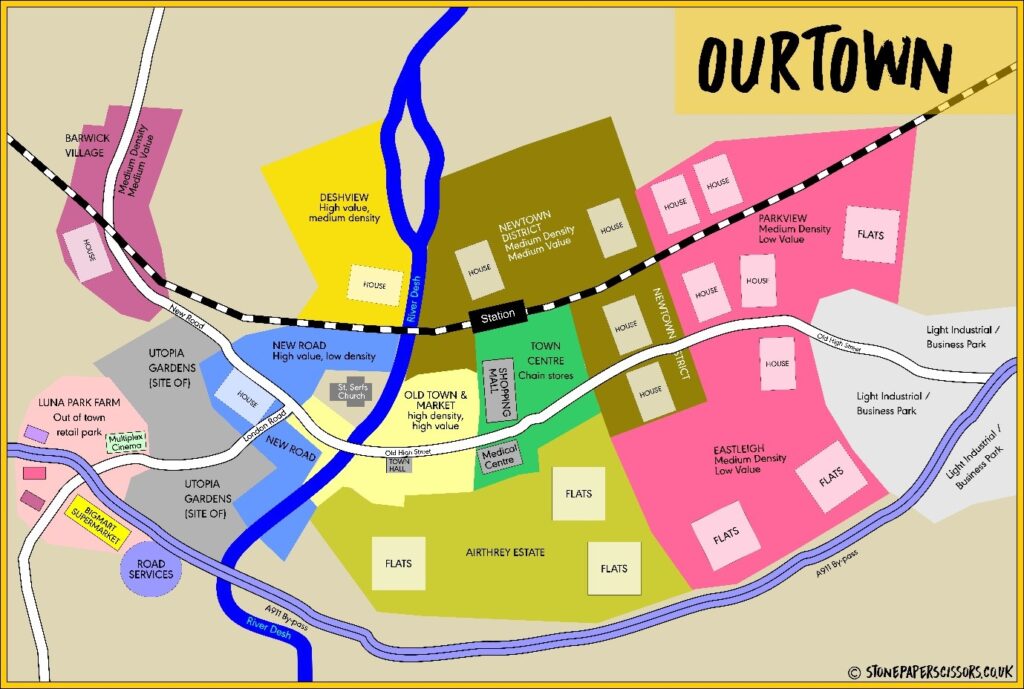

Players will build their starting house, and place it on the community map – after all, we can’t talk about our home without talking about where it is, what is (and isn’t) easy to access, and how we’re connected to those around us.

With Susan’s life set up, players will then move to the next phase: life changes. During these two phases players recieve an update to their vignette giving them more information on the person they’re playing for. These updates introduce new challenges, much as life does: an accident, a new health diagnosis, or some other chaotic event that means the home they’ve built is no longer quite right for the person that lives there. Now it’s up to them to be creative and think of ways to adapt the home they’ve built to meet the new needs of its resident.

Each card, each adaptation has a cost, and an effect on either the cognitive and physical environment. The goal of the team is now to work together to create a home that works for the person who lives there. They might choose to spend their own budget, to request funding from their “local authority” (the facilitator), or move house entirely. The solution is up to them – and hearing how different teams approached the challenges they faced is a huge part of the final stage of the game, which gathers the players from every team together to give them a chance to discuss what they saw, what they thought, and what they’ve learned.

What did DesHCA find?

Playing Our House provides players with more opportunities to interact with one another, think critically and creatively about the challenges in front of them, and reflect on their thoughts, beliefs, and biases about ageing than other less interactive methods. It prompts people to engage with things they usually don’t think about, and offers an opportunity to think creatively about how they, too, might prepare for and respond to the challenges that await all of us in our later years.

The goal of the serious game was always to create a tool could give people space to think about the future in a critical and creative way, an opportunity to improve their understanding of the systems, processes, decisions, and people who play a role in creating more age-inclusive homes. Our House does this by using the mechanics of game play, the cards, the board, the teamwork, to break people out of their usual way of thinking and encourage them to look at the situation in a new way so that they can better understand not only the opportunities for improving homes with age-inclusive design, but the barriers to adaptation and negative impacts of living in a home that is no longer accessible to you.

The WP4 team has published a paper outlining the development of Our House and the insights gathered from the 100+ participants who have played so far. You can read it for free here.

If you are interested using Our House, we would encourage you to email Professor Vikki McCall to discuss access to the game.